Phở - a translation of Nguyen Tuan's essay of the same name

And a much needed exposure to the dish's rich, yet often ignored, background

Phở is probably the most recognizable of all Vietnamese food worldwide, so much so that I feel an introduction to what it is is redundant at this point. There are restaurants everywhere that sells phở: in Singapore, in broader Asia, in the US and Europe. Phở is the default dish of Vietnamese restaurants globally. Many of my friends, to my delight, have taken a liking to it. Recipes for phở are abundant online, from traditional to fusion, embraced by Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese alike.

But while phở has an impressive presence, I don’t think much of our literature about phở has been accessible to English speakers. It is not enough to eat phở, it is crucial to understand what the Vietnamese people, and especially the Hanoi connoiseurs, think about the nation’s dish, for it is more than a dish; it is also the nation’s soul. Phở, muse for generations of writers as it is, deserves to be understood by non-Vietnamese to the same intensity and endearment that we do. I thought, why not take into my own hand the task of translating one writing about phở?

Here, Nguyen Tuan - one of Vietnam’s literary giants - writes about phở in his signature impromptu style, meandering between the legends in the world of phở. He wrote it in 1957, during a work trip to Helsinki, Finland, when Northern Vietnam was building socialism and fighting against the America-backed regime in the south: phở, therefore, is as much a dish as it is the reality of Vietnamese people in a dire time. He is particular about the dish itself, about its traditions, about its tastes, about its ever-changing nature - some opinions are rather controversial! He is passionate about phở as an emblem of Hanoi, an ambassador for Vietnamese people, an inseparable reality of the Vietnamese people. He is observant about the people behind phở, both the hawkers and the diners. As a true-blue Hanoian, he is prideful, fussy, and passionate when talking about the city’s famous food. The author is unrestrained, and the piece is not exactly succinct, but it is a fascinating read. In fact, some of its content was still new to me, as someone who had enjoyed the dish all the time growing up.

I imagine it would be a fascinating alternative to my international friends, whose exposure to writings about phở is mostly restricted to cooking blogs, a recent phenomenon that merely covers the very superficiality of this celebrity dish.

The piece is slightly long, and rather loose in form, so I have taken liberty to trim some passages.

Opening the piece, the author is in Finland with a group of other Vietnamese, dissatisfied with the local cuisine and yearning for the flavor of home.

[…]

Phở is a dish of tremendous collectivity. Whether you eat phở sitting down or standing in the middle of the diner is not for judgement. Phở is a dish of the common folk. Workers, farmers, soldiers, intellectuals, all the strata of society, urban or rural - barely anyone does not enjoy phở1. Many a Vietnamese citizen since infancy has savoured the taste of phở; the sole difference is that the bowl of phở from one’s innocent childhood didn’t require complication, didn’t need pungent onions, sour lime, or spicy chilies. For poor families, even meat was oftentimes optional; after all childhood phở was simply noodles and broth.

Phở is a versatile meal. Morning, noon, afternoon, evening, night, phở can be eaten any time of day. Eating a bowl of phở is like brewing some tea when chattering with one’s mates. Perhaps nobody has the heart to decline a friend’s invitation to phở. Phở affords the gentleman to express his kindred towards his peers, however suitable for his budget. The other ingenuity of phở is its all-year-round profundity. On a sunny day, eating a bowl, sweating slightly, catching a gentle breeze through one’s face and back, one feels as if fanned by nature. On a cold winter day, eating a hot bowl, one’s frigid lips suddenly feel rejuvenated. For poor folks on a cold day, a bowl of phở is like another layer of clothes. On a wintry night, eating a bowl of phở, one feels as though he had just swallowed a blanket whole and can sleep peacefully until it was time in the morning again to go to work. To conjure up a Vietnamese winter with proletarian snapshots, I am convinced nothing is more poetic than the fire-stove of a phở joint in a crowded passenger terminal encircled by people eager for their own bowl, their shoulders slightly hunched, their bodies jostling like excited kids. For Tết, every household would have bánh chưng, cá kho, and thịt đông2, yet many would serendipitously receive their New Year greetings at phở stalls that reopen as early as the second day of Tet.

Hanging out with phở enriched my writing voice. I used to believe that xương xẩu is a double-word3, xẩu being a mere echo. The phở stall uncle added another word to my repertoire. Xẩu is different from xương, the former referring to the ends of broth bones with small pieces of meat and tendon still stuck on. I saw coolies ordering a glass of alcohol and a bowl of xẩu. I also learned from another uncle to refer to brisket fat, that marbled - yet not excessively fatty - soft and crunchy piece of meat with a waxy elasticity, as cánh gầu; to speak of the meat so fresh that upon touching it dances under the blade quả thăn4. In a past Vietnamese novel I remember a story titled “The Phở Stall Man Marrying a Geisha”. I heard a prostitute lamenting her life had lately been “like pho with mushy noodles and congealed fat.” A cold phở truly is more regrettable than a courtesan’s life being swindled away by pimps. Our language is marvelous! It is said the word phở comes from the Chinese niuroufen, and we Vietnamized the syllable fen to become phở. Phở was originally a noun, but it is also an adjective, as in the phở hat. Our language is marvelous!

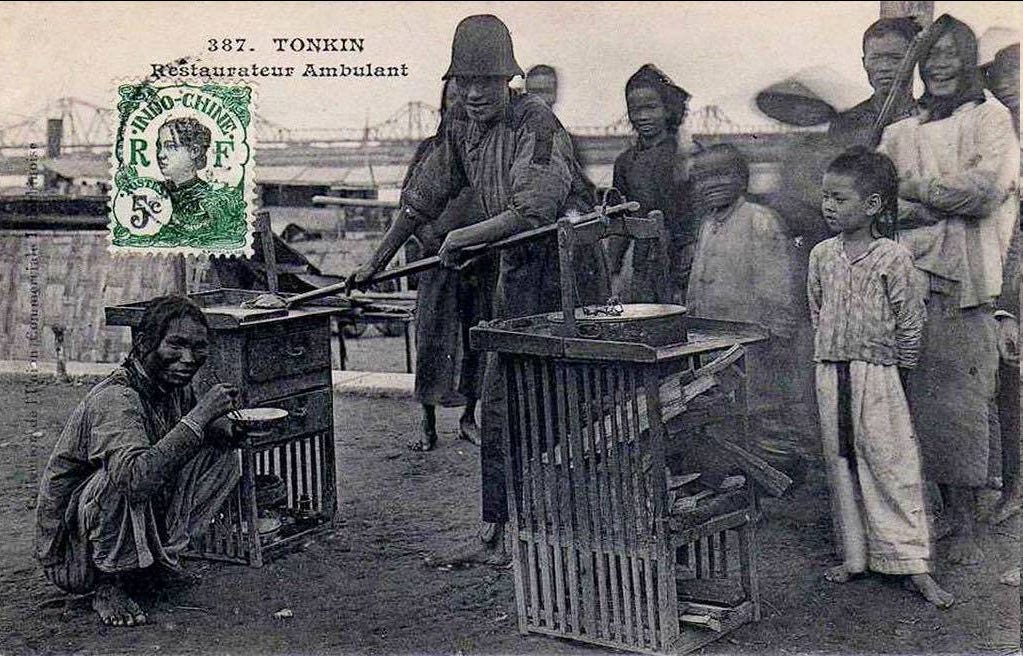

What is the “phở hat”? Now only by reconstructing the image of the authentic phở gánh5 hawker can we track down its origin. Phở hawkers used to have their very own dominion; whether on this or that street, or even in the back-alleys, the buyers would know the seller personally, and the seller would know the dining habits and quirks of all the area’s residents. These territorial phở hawkers even know how many people were in each household, and the date of each of their feasts6. They were simple businessmen, often dressed in a felt coat with a yellow resembling the horseshit from French-era peacekeepers; on their head, a tattered hat, usually a misshapen felt hat with a lost cap or torn sides. These hats seem to be improper and meaningless on anyone but the phở hawkers. That phở hat also serves as a assembly ground, an insignia of trust. Those with those torn hats would usually make delicious phở, or at least edible.7 The phở gánh with the phở hat has become rare lately; only phở carts, ship-shaped carts with chimneys8, phở stalls and restaurants remain. On the painted steel toys for kids sold on Hàng Thiếc Street, the figure of the phở gánh hawker persists, the wind-up engine creating the up-down motion of the arm with the knife.

Phở has its own conventions. One example is the naming of phở stalls. The names are often monosyllabic, using the first name of the owner or their kids; for example phở Phúc, phở Thọ, phở Trưởng Ca, phở Tư… Sometimes a deformity on the hawker is intimately referred to by people, becoming the stall’s name: phở Gù, phở Lắp, phở Sứt…9 These bodily shortcoming turn into marks of trust in the profession, popularized by the connoiseurs’ word-of-mouth. The common folks, especially Hanoians, have plenty of nickname ideas for their beloved. Wherever the pho hawker sets up his stall, they would use that same location to refer to the person: phở Nhà Thương, phở Đầu ghi, anh phở Bến tầu điện, and phở Gầm Cầu… Sometimes people name them after a peculiarity in their clothing. The airplane cap associated with the past French-era phở stalls became the name of a renowned phở joint in Hanoi. Perhaps because of their affinity to the middle and lower class, just like barbers, and baristas, the name of the phở stall is a tidy single syllable. I haven’t seen any popular stalls with a long-winded name, such as some phở Tôn Thất Khoa, or some Phở Trần Thị Kim Anh. The curter the name, the worthier it is of the consumer’s trust; the monosyllabic name is as clean as the knife slicing through meat. Even in the grandiloquent Hanoi, phở stall names are plain, devoid of pomposity. Should someone, in a burst of pretentiousness, name their stall Thu Phong, Bạch Tuyết, or Nhất Chi Mai, I would never visit them. The phở profession has its own order.

But there are things that want to destroy the orders of the phở profession. In my opinion, phở’s fundamental rule is that it’s made of beef. There might be plethora of meat, seafood, or birds that taste better than beef, but phở requires beef. Is it because people want to rebel that they are making duck phở, char siu phở, mouse phở? At this pace of experimentation there will be snail phở, frog phở, goat phở, dog phở, monkey, horse, shrimp, carp, pigeon, lizard… deranged, deranged phở. Maybe then people will eat some kind of American phở. In the 1945 famine, at the bottom of the era’s phở broth pot, in Haiphong and Hanoi, there were pots with children’s hands, but that’s a different story.

[…]

And there is also chicken phở. For the sake of switching up the conventional flavor of beef phở, having a few bowls of chicken phở in one’s life is alright. But there is this chicken phở stall in Hanoi that spurs many Hanoians’ dismay. This guy sells in the early morning, with people always flocking over to eat. The hawker, prideful as an aristocrat, cleverly chose a corner named after a royal madame to set up his stall! Have to admit, the chicken there looks divine. There are folks praising his unsurpassed talent, and that his hand slices through the golden fat chicken like a surgeon with his intimate knowledge of the bone structure. The head, the lower leg, the neck, the beak, he nonchalantly throws them into a box, not to be disposed of, but there perhaps may have been certain neighborhood alcoholics eyeing them for a snack later. Frankly, when one has a bowl of chicken pho where people dare pay up to 1500 dong10 for a bowl, it is hard for it to be bad. Stand around on a morning to watch people savoring their chicken phở, hasty, impatient. Some get the stomach, some get thighs, red meat and not the sour white meat, some get the fat, the butt11, the wing-tip. Eating is suffering12. On that pavement, agitation surrounds the hawker, who is as aloof as the British Empire, who sells with authoritarian disdain: the diners have to get the bowl themselves. Some brought from home an onion, a chicken egg…, they crack the egg or peel the onion in their bowl to mark it, pushing the bowl to the hawker, smiling to him, reminding him sweetly as if afraid he would forget or mistake their order… Alongside the chopping sound of the chicken phở hawker, occasionally there is the rumbling of a motor engine driving over for breakfast, lacing the steam with a gasoline smell. Someone slurps on the bowl, recounting this hawker’s golden age, that in the era of colonial and puppet governments, cars would form a snaking queue here for breakfast; many ladies of Hanoi society would hold the bowl of chicken phở, their ten fingers sparkling with golden and diamond rings; the piece of chicken butt gets even more seductively moist.

In the Resistance war there are famous phở hawkers on liberated land like phở Giơi, phở Đất, phở Cống (the names remain monosyllabic), but there are also bowls of pho that are improper, yet heart-warming. For instance, there was the phở in military ground bases, made within the facility. Several central offices would kill a cow together for monthly rations. The beef was there, the bones were there, but there would be no fish sauce or herbs, and the noodles were the dried type. Yet they make phở. The phở feasts of Sunday afternoon on the riverbank near the base make the best headlines for internal brochures.

Apparently Thach Lam also used to talk about phở, but he was rather simplistic. In the start of 1928, in Phố Mới, formerly Đồ Phổ Nghĩa after a colonial figure, there even existed a hawker who used Chinese five-spice, sesame oil and tofu. But his experimentation was short-lived, as the people’s taste was not as degenerate as the creator’s. The people still demands phở’s antiquities. Nowadays there are people even putting Hoisin sauce in phở, but that’s their moneyed privilege; whatever modifications one desires, the restaurant would try to satisfy within the limits. Many say that phở tái (with medium-rare meat) is healthier than phở chín (with medium cooked meat). Probably. For health’s sake, one could also have some Soviet Pantocrine or Chinese medicine instead, and the results would be much more prominent than eating phở tái. Frankly, to eat phở properly, one must eat cooked meat13. Additionally, in aesthetic terms, the sophisticated will always find the cooked piece of meat better looking than the raw one. Indignified phở hawkers would frequently pre-cut the cooked meat into haphazard crumbs to be sprinkled on the bowl when ordered. That might not bother the customer in a hurry. Yet in the same crumb-chopping stall, the hawker is very discriminate towards diners: for the regulars, people whose name he might not know but whose eating habits he has internalized, once those discerning guests set foot inside, he would instantly start slicing his special cut of cooked meat like the crunchy flank, the lean flank or the fatty brisket, slicing up thin yet broad sheets, with the calm contentment of someone showing off his expertise. Any man eating phở with an inclination for painting would want to make a still life. Sometimes the phở hawker gets grumpy with his wife because his cut was subpar. Another hawker, formerly at a roast poultry joint in the times of Hanoi occupation, is also selling phở and enjoys talking the craft of the knife with his customers, all while swinging his knife. “Chopping a winged bird is difficult, yet nowhere near chopping a boneless cut of beef. Much as I taught them the women in my household just can’t do it, they can only cut cakes.”

A Hanoian pseudo-intellectual once expressed his concern that once we progress to a full-fledged socialist economy and the decentralized economy disappears, we would lose traditional phở and would have to eat phở in a carton, each time putting the carton in boiling water before eating and that the noodles would all be mushy. To which, right in the phở stall, someone rebutted: “To hell with you! Stop being a doomsayer. Phở is now growing strong in Hanoi, in total around two thousand stalls. As long as Vietnamese people exist, the bowl of phở would remain smoking hot, whether future or present. Our bowl of phở can never become packaged. This Hanoi citizen would have half a mind to tell you a thousand times over that no, no, we can’t have that savagery.”

In the past, the world of Hanoian phở was full of its own distinct characters. Pimps and prostitutes, students, soldiers, clerks, judges, gamblers, shopowners, transport workers, freelancers… There would be mercenaries at the phở hawker, who upon paying flip over their red hats to reveal a pair of jacquard14 pants stolen from the brothel; they would hang the pants at the hawker as a form of payment then flee… There are eccentric, filthy rich men that put bread into the fatty phở broth, calling it ‘commoner’s Western food’. There are rebellious women who mix stale rice into a hot bowl of phở, eating eagerly, yet an outsider witnessing that would only see dreadfulness. There are homeless people on the streets, the kind who run errands at the black market, who, when calculating commission, use the five-cent phở bowl as legal tender, saying: “Everything is going well, sir, just give me a hundred five-cent bowls", etc.

[…]

We sit on the edge of a lake in the outskirts of Helsinki, reminiscing of the motherland’s bowl of phở; for that delicacy of our amiable people in Southeast Asia, we discovered phở’s abundant virtues, a solid foundation for a theory of phở. A few months after upon returning, setting foot in Hanoi, my first meal was phở. Afterwards, on my frequent phở dates, I discovered that in the mind of a friend the dish has become an obsession: “We think phở is delicious, but before deciding on its ethnic significance, should we first consult our international friends? What do our Soviet, Polish, Hungarian, Czechian, or German friends15 feel about the Vietnamese phở? Have they had the chance to try? They have listened to our folk songs, they have seen our country. But we also have to make them “see” phở, because phở is the spirited song of all the Vietnamese people’s sincere and unassuming souls.” On another date, also in a famous phở stall, I overheard a snippet between two girls in a nearby high school: “This stall is amazing. Do you know if President Ho and the Party leaders16 like phở? - How would we know? - Hey, if ever they grace any phở stall, the hawker must be exhilarated!”. The two pull out a pocket mirror to check if their teeth still have any green onions or coriander, and giggle like a flock of bird around the table. That conversation helped me understand more about phở, and things much greater than that too.

Lately, we often talk about the Vietnamese reality, about Vietnamese problems, about Vietnamese characteristics in progressing our society forward. I believe in the plethora of Vietnamese people’s realities, there is one few have the heart to forget, the reality of phở. The reality of phở is intertwined with the grand reality of the people. In a bite, one imagines all the noble happiness of our vast, bountiful, and beautiful motherland. I see our motherland with colossal mountainous heights, with long serpentine rivers, with the vast coastline, with brave Vietnamese building our glorious history, with magnificent works of labour like the Dien Bien Phu battle, but besides those, I also see that our motherland has phở. In the warring years, the enemies flew above bowls of phở; there were bowls one had to hurriedly slurp in the darkness of night, then wipe one’s mouth with one’s sleeve to climb down the shelter; there were bowls that were bombed, the noodles all mushy, the diner never to return again. Back when I was working in enemy controlled territory, I can never forget the night phở hawkers encircling the guerrilla headquarter; hot bowls of phở, eaten after days of trespassing hostile territories, had a most special flavor; later, as they raided the area and destroyed all stalls over the dike, I wondered if the phở hawker that night emerged alive or dead. In another occasion, on a campaign with the Lung Vai unit, I couldn’t forget the marches with the head of food supply; he had so much cumbersome kitchenware that the troops would refer to him as the phở hawker of the unit. Before the war of resistance he had a phở stall; now that peace has been reestablished, is he still alive to reopen it? Images of phở in those taxing years resurfaced. Now, eating my piping hot bowl of phở in peace, in daytime, I owe my gratitude to so many. Then my emotions around phở abruptly blow up. I think of verdant livestock pastures in the Thai-Meo autonomous region, the herds of cows in Lang Son and Thanh Hoa devouring up the land’s fresh grass. Rice harvests have been good for the late few seasons, the noodle dough smooth and sticky. On the outskirts of Hanoi sit boundless fields of delicious greens, of herbs perfumed with the flavors of the terroir.

[…]

A very conscious decision to write Vietnamese word with full diacritic, so that pho is not mistaken with a more vulgar similar word.

a square rice cake with mung bean and pork belly filling, a Northern-style braised fish, and jellied cooked meat respectively, all traditional Northern food around Tết

Vietnamese uses double-words to ornament nouns and adjectives. For example gắt gỏng means irritable, but gắt itself already has that meaning, gỏng means nothing by itself.

roughly ‘brisket-blade’ and ‘round tenderloin’, but these are very figurative language that isn’t really used by normal people

A travelling pho stall, the traditional way pho was served. The hawkers carry the pot of broth and ingredients on his carrying pole, then settle down on a pavement to sell his food.

originally ngày giỗ - a death anniversary of an ancestor in the family where people would gather and have a feast.

Knowing Nguyen Tuan’s fussiness with food, one can infer that edible means pretty good on average

Have absolutely no idea what he was talking about here

Hunchback, stutter, and snaggle-toothed, respectively

At the current price that’s about

This is actually a delicacy since the meat is very fatty and flavorful, but it needs to be cleaned well.

The original is a wordplay on the idiom Miếng ăn là miếng nhục, nhục meaning both ‘meat’ and ‘humiliation’

This is very controversial on Nguyen Tuan’s side: most people I know prefer the raw meat

originally quần lĩnh, pants made of a type of woven fabric usually worn by rich people

Communist countries that are allies with North Vietnam during this time

Ho Chi Minh and the officials of the Vietnam Communist Party