Brasília: a monument for the future

Brazil's capital is a highly eccentric city, and the country's very own vision of utopia

Brasília. The opus magnum of Oscar Niemeyer, Builder of Monuments. An open air architectural museum erected in the middle of desolate Brazilian highlands. A beacon of Brasileiro hope, represented by a bold - albeit faltering - vision of modernity. Brasília proper feels less like a city than an exhibition, a carefully curated assortment of artworks, designed not to be a human metropolis but a bulletproof glass case for the country’s leaders - yet through time, human interaction has slowly perverted this artwork into its natural state. Here lies the seemingly unquenchable vision of modernity that the sixties had promised the world, bogged down by the modernity of sixty years later.

I. The aircraft of the future

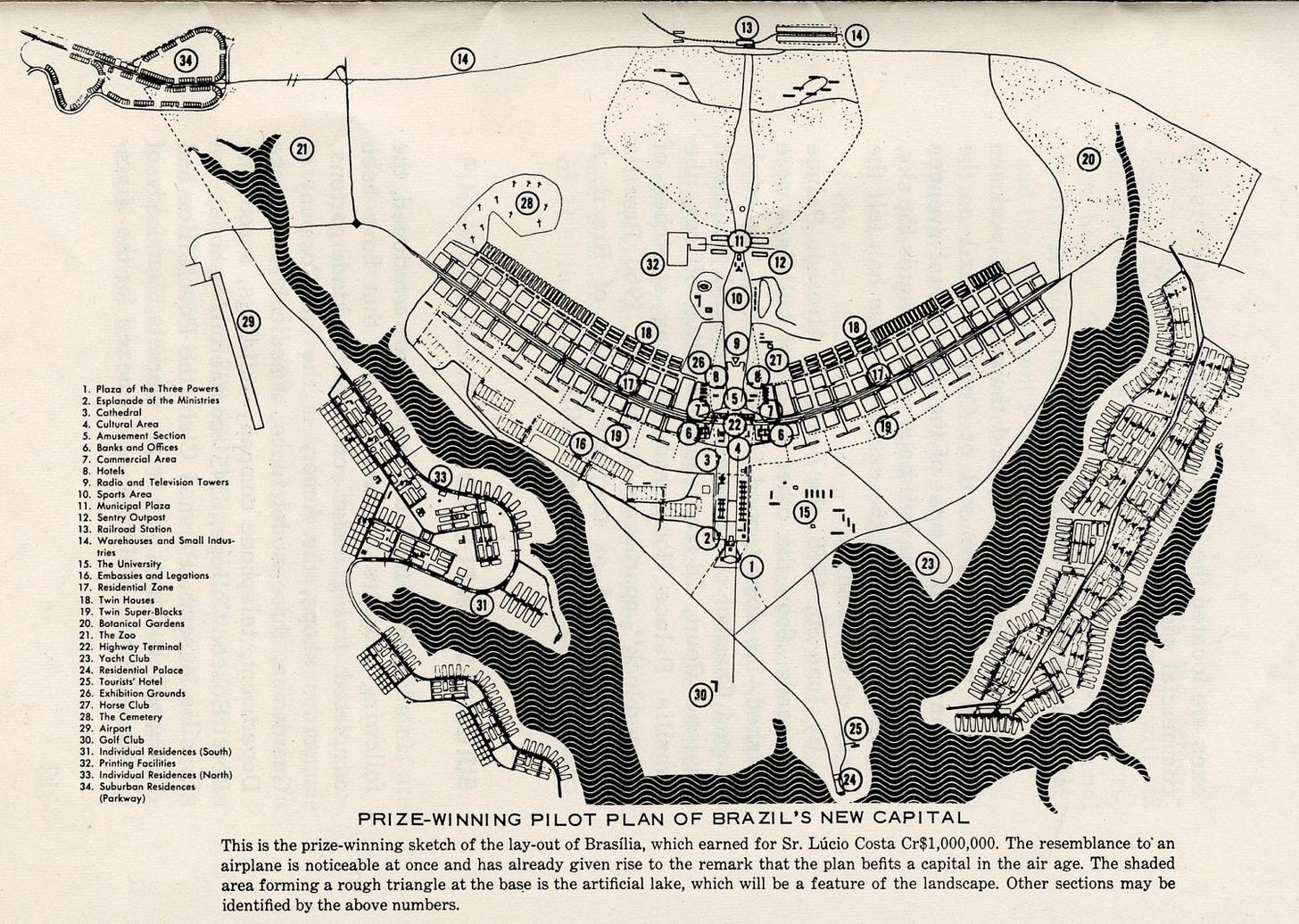

Brasília is shaped like a plane. Such a simple yet striking configuration encapsulated the city’s principle of design: grandiose, utopic, and highly symbolic. As such, it is also the least ‘Brazilian’ city possible. It is sterile, artificial, and uneventful. On the other hand, it is also orderly, serene, and (comparatively) safe.

Looking at Brasília in seclusion, one might get the impression that it is an overambitious folly plan of artificial progress, a waste of resources by politicians trying to build for the sake of building. However, having been in São Paulo, even for just a week, I have come to understand its ambition. Rio, much as it is the ultimate beacon of Brazilian flamboyance, was terrible as a national capital, being crowded, vulnerable, and suffering from a reputation of vice and inequality. By moving away from Rio, Brasília, built from scratch from a piece of barren land in the undeveloped midst of the country, represented a new beginning. Brasília was a chance for Brazil to exert itself to the world, to build a wonder of its own. In a sense, that ambition still resides here, even in the resolute and resounding name of the city, one that was not invented by the Portuguese colonialists.

As the new federal capital, Brasília was destined to be full of towering iconic buildings. But it would be simplistic to think of Brasilia as only its monuments. Costa’s plan of what is now known as Plano Piloto is a comprehensive idea of utopia. The plane’s wings are designated for residential use, and are composed of ‘superquadras’ - huge blocks encompassing residential, commercial and service buildings that are supposed to be self-sufficient. Lower density buildings were to be erected in Lago Norte and Lago Sul, two distant areas to the North and South of the artifical Paranoa Lake. Such was the Brasilia that was supposed to be the future, whether its ideas still hold up or not: some, like the car-centric and monumental design of the city, had fallen off, while others, like the concept of comprehensive planned blocks, still stand the test of time.

II. Architecture as installations

As Lucio Costa built the aeroplane of the future, it fell to Oscar Niemeyer to adorn it with buildings. And so he did. As if Niemeyer’s buildings are not already distinctive enough on their own merit, the builders of Brasilia have ensured that they are contextualized in such a way that they appear completely disingenuous in their natural surroundings, and isolated enough to accentuate their monumentality - in fact this is the entire concept of the Eixo Monumental (Monumental Axis). Eight lanes of traffic flank a central grass plaza, which is hilariously barren as if to discourage any pedestrian, but which also evokes the vast cerrado on which the city was constructed, whose iron-red streaks were peaking out beneath the poorly trimmed lawn.

From most of the city you would be able to see the National Congress, with its twin towers shaped like a colossal bookmark, anchoring the gigantic spaceship of senators to the ground. In fact, the towers are of such scale that it is rather easy to ignore the base, where Niemeyer’s signature curves are more prominent. Its myriad of windows felt like the compound eye of a mammoth insect, keeping surveillance over the vast landscape.

Almost antithetical to the Congress in geometry is the Metropolitan Cathedral. Brasília’s most famous structure is of much humbler proportions than the others - rather like how the Mona Lisa looks minuscule in reality - yet it is no less striking. On the sides, its spines protrude out in naturalistic fashion, like a sea creature's exoskeleton, a crooked crown of biodiversity. Inside it are stained glass panels, which by its size are underwhelming compared to more traditional churches, but since they are located at such a flat angle, all the churches interior felt submerged by the oceanic hue that filters through Brasília’s garish sunlight. There is no regular crowd in the church due to its location - the only congregation you can see is flocks of Brasileiros from all over the country paying a visit to what is probably their country’s most iconic modernist building. Outside the cathedral, an eccentric razor-shaped carillon heightened the iconoclasm of this peculiar church.

Next to it, the younger National Museum clearly drew inspiration from space exploration with its Cronian halo. Its round and spotless surface would have already blended seamlessly in an extraterrestrial setting, yet the scraped paints and discolorations on its pale white created an even greater resemblance to the moonscape. Then you walk into its dazzling, planetarium-esque interior, and the immense heat hit you because there was no air-conditioning.

The other buildings are mostly a melange of harsh, totalitarian rectangles - very emblematic of the time - and Niemeyer’s softer, more fluid geometry. A case of harsh white outline the structure, and then gentle parabolas carve out it’s interior. One can see this the best in the star-like motifs that defined the Palacio do Planalto and the Supreme Court (as well as the Palacio da Alvorada, but alas our neighbor President Lula valued his privacy and so his residence is off limits to the public). The stars ripple gently outward and inward. Even in structures that are more uniformly rectangular, like the National Library or even the Palace Hotel, where I was staying, one can still detect hints of that signature complexity, whether in the form of intricate lattice grids, or gracefully angled panels.

The shape of Brasiliense structures are simultaneously monumental and miniature-like: given their sweeping minimalist geometry and lack of ornamentation, they can be downscaled without feeling too busy or overwhelming. In a sense, the abstract principles that have guided many contemporary artists of the last century, including Niemeyer, makes the buildings eerily similar to those small, enigmatic sculptures you see in a modern art exhibition. Plus, there is little trace of functionality in their shapes - a point that critics of Niemeyer often brings up - which reinforced this exhibition analogy. An art piece foremost, and a building second.

In a modern art gallery, one walks amidst installations that are placed at great distances from each other, with nothing but white walls filling the space between them, just as in the colossal exhibition that is Brasília. Here the white walls are replaced by an agonizingly blue sky and a few feeble trees; as the installations are blown up to grand scales, a viewer is no longer a god but an ant trying to find his way through the place, under the scorching sun of the cerrado. One doesn’t simply admire the art; one is engorged by its formless maw.

The monuments of Brasília have an especially evocative power. You could say this may be because I have been dreaming about seeing them in person for quite some time, but even then, the sheer timeless, almost alien look of these structures never ceased to amaze me. These architectural installations look nothing like what would immediately come to mind when people think of ‘buildings’, even now. From the Almeida dos Estados, with the towering National Congress behind my back and the vast Esplanade of Ministries in front, I couldn’t imagine what the people of Brazil must have thought when the buildings were completed sixty years ago. President Kubitschek made a big promise when he said he would achieve fifty years of development in five years, but were I there back then, I must have thought that a century had passed.

III. Temporal art

Brasília! You only came to being from the pristinely encased sketches of your fathers because of the countless daring humans that believed in the idea of you. And yet the same human that believed in your holy white light is the same human that perverted you, transformed you, for they know not but the ways of the past while you are conceived with the future.

Even now, Brasília still looks like the future, if only a deviant branch of our timeline. It’s idiosyncrasy is still ever fascinating. But that version of a future, exactly because it is so uniquely far-reaching, is now stuck like a fossil in time. I always find it funny and ironic the way futurism itself is such a non-timeless aesthetic: I imagine our kids would sneer at the solarpunk bio-futurism of today, with tall glass towers, spaceships and greenery, as a form of antiquated humor only alive in those ‘Society If’ memes.

The biggest mistake the dreamers of Brasília made is that they treated it like an installation: a space where agents sit in a silent, observant equilibrium, where the artist and architect is God, and all his intentions obeyed with piety. Yet humanity is all but inert. Brasilia broke from its original form, as people from all Brazil flocked to the new capital city, and as Costa’s utopic superquadras soon proved too imprisoning for human nature. The city of three million has ballooned far off its original capacity. Suburbs propped up, extending the superplane into an amorphous, encumbered shape. Plots of land on the Plano Piloto remains staggeringly empty due to the lack of new development; meanwhile, outside of it, an organic, more human city is taking shape.

Brasília’s biggest criticism was how car-centric the city is, even by South American standards. Having walked through the incredibly shelterless main axis, I am inclined to agree. That is just another facet to Brasília’s fault, which is its incredible insistence on carving out a future to its vision, but that is perhaps the most apparent sign that the city had been a product of its time. The suburbs of Brasilia are denser residential neighborhoods, and they’re even building a metro system to connect the Plano Piloto with the outer suburbs. This is a departure from Costa’s vision that there would be no need for a metro and that buses from a single main terminal would be able to service the whole city in perpetuity!

Through all these upheavals, only the main axis remained relatively fixed in place. Its structure is still devoid of density, piously following the dogma that the Fathers have decreed sixty years ago. In some areas, that piety had lapsed into disrepair. The unkempt lawns and the emptiness of the city parks. The vast emptiness in the original Hotel sector1. The aging dust on the facade of the ministries. There was barely anyone on the Eixo Monumental on a weekend: I was merely accompanied by a few Brazilian tourists. Silence had fallen on the revered monuments, just like in an art museum. In a sudden, the grand monuments of Brazil’s rulers felt quaint and distant, like a butterfly in amber, while the roaring of a new order can be heard somewhere beyong the horizon.

Artworks, no matter how timeless they claim to be, have imprints of time all over them. However, while an artist’s work can be encased in time and beloved just as well under that lens, a city is always in the present. Last year I wrote about how Melaka seemed trapped in the glory of its old time, pitiably unable to reinvent itself as a modern city. Brasília’s conception was much more recent; still, a cynic can readily see signs of its decay.

IV. City of God

People say Brasília was heralded in a priest’s dream, as a modern utopia in the midst of the Brazilian highlands. That itself lends the city an air of mythology. And while purpose-built capital cities are no longer a novel idea, Brasilia felt much more religious, more ritualistic than others of its kind. People have criticized Brasilia of being soulless; me, I find it highly romantic.

In a world of cities built first and foremost for the human body, Brasilia made me feel almost un-human. The way its vast expanses of bare grass make no sense on the ground, the way its modernist structures are bare and impersonal, the way its design makes little sense for the pedestrian. I have written of Brasilia as an exhibition, but the feeling of walking through these monuments were something grander than merely observing a beauty. The structures in front of me weren’t buildings but altars; the idea, the deity representing them were embdedded into their eccentric outlines. On a weekend, as most public servants are absent, these empty altars don’t seem to be workplaces for people anymore, but mechanisms for an esoteric, unfathomable bureaucracy, rather Kafkaesque, I might say!

Everyone says that Brasília is designed for cars. The act of putting these soulless mechanical creations on the pedestal therefore must have stripped away any of the city’s romance and poetry. However, I personally believe that the car-centric-ness is purely a manifestation of its ultimate devotion. That Brasília was designed for God. Its deity is not the traditional conception of God, but a god of modernity, one whose Cathedral deserved a thorned crown and whose service is called forward by mechanical bells. A god whose touch is tender as the wind on the shores of Lago Paranoa, but whose gaze is merciless as the midday sun on Eixo Monumental. A god that, in all his imperfections, is ultimately benevolent.

On the Esplanados de Ministerios, the Grand Cathedral (and by extension, the Metropolitan Curio) was the only structure that is not a ministry. Back in the time of Portuguese colonization the church was such a ministry in everything but in name, its tentacles infiltrating every nooks and crannies of culture. Maybe that is a way of signalling that Brasilia secretly had a ministry dedicated to something above, something more transcendent than the everyday toil of civic servants. I, like Niemeyer, am an atheist; yet we are similarly beholden to the sacredness of humanity. Peasants in the Middle Ages had built churches so they have something transcendent to look up to - and here, what is more transcendent than a peek at utopia - even if that utopia ends up being deceptive?

In Brazil, the name City of God would inevitably prompt and association with the Cidade de Deus, an infamous unsuccessful favela relocation scheme in Rio de Janeiro that ended up only creating another favela. A dishearteningly common tale of unsuccessful urban renewal. Of course, Brasília is nowhere near a favela, but many contemporaries had begun to consider the city a failure. The God that it had dedicated itself to, working in his mysterious ways, had allowed Brasília to stray far from its original vision. Yet does that mean that there is no God?

It is easy to think of governments as corrupt and horrible - Brazilians have said that the only bad thing about Brasília is its politicians. I am by no means saying that such a thinking is wrong; in fact, they are probably right. Yet, a church is corrupt and horrible in many similar ways; why then, do we still gaze up to its magnificent stained glass and painted ceilings like moths to a fire?

Across the worlds, new capitals are still being constructed, for the same reason that Brasília was envisioned sixty years ago.2 Even when its ideas had fallen off, Brasília still represented a pure, religious reckoning for me, not just from the timeless, iconoclastic beauty of its monuments, but from the sheer audacity and hopefulness of its creators as well. Humanity shall dream! And our light shall keep on burning brilliantly, even when dust begin to gather on our fossilized bodies.

Rather relevantly, the Palace Hotel Brasilia was burned down in a fire in the eighties and fallen into such a state of disrepair that only through activist pressure that it got reconstructed, opened back in 2006 and that I was able to stay in a part of history.

Note from the editor (Joshy): If you are based in Singapore, and are interested in the journey of the new capitals springing up in Southeast Asia like Putrajaya in Malaysia and now Nusantara in Indonesia, check out the Capitals of the Future project by my friends at the Asia Research Insitute, they have events and roundtables from time to time where scholars from the social sciences and humanities reflect on today’s ‘Gods’ of nationalist modernity and Global South utopia. https://doi.org/10.25542/4jdh-4h27