Ryuichi Sakamoto - Sound and Time

Capturing a masterful exhibition on one of music and visual arts' greats.

One of the highlights of our China trip was our visit to the MuMu Art Gallery in Chengdu, as recommended by a friend. There was only a single exhibition on - Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Sound and Time, where various installation artworks that the late composer has made in collaboration with other artists are collected and displayed. Such is an exhibition that forced me to think of what makes a good art exhibition, and how to memorialize such complex, big-scale works when normal techniques become woefully inadequate. As you soon shall see, whatever photos I manage to take would fail to capture the essence of the magic.

i. space

Walking into the exhibition after the unexpectedly expensive 160 yuan tickets-for-two-after-discount, I was instantly engulfed in darkness. A singular screen dominates the wall, on it vividly dancing light particles. A control board centered the room, its knobs and buttons inviting the audience to mutate the sound; as one dials up or down, the intensity of the particles on screen would change accordingly. One can even switch between multiple modes of visualization - a striking red nebula, a staticky white powder, or a harmonious, mellifluous overlap of circular shadows.

An exhibition is a space, but sometimes it can be a world. Shunning all the noises and lights of the outside, all that is left is a personal, private space. Utter darkness allow one to immerse in the artwork’s light, while excellent soundproof isolate the pieces and pace the journey. Such an isolation heightens the senses, allowing the audience to be fully taken into its realm, to grapple with its sound and time.

ii. three overlapping times

As suggested in the name, a major theme of the exhibition is time. Saying an exhibition deals with time though, is rather redundant. Aren’t all exhibitions, even those without time as focus, dealing with temporal manipulations of some form? In the brief hour or so in a typical museum, a visitor usually would have travelled to multiple periods of multiple artists’ lives through their work. In looking at a single artwork, one traverses the months, or even years, that lead to that artwork taking form. Sound and Time has a similar responsibility: to distill a life’s work in installation of an artist to a single experience.

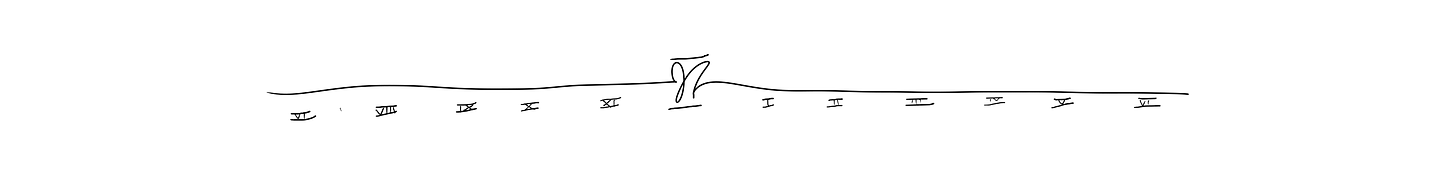

What sets Sound and Time apart is the inextricable nature of its installations from time, for in sound, there is fundamentally time. Three axes of temporal movement coexist and overlap: time in the musical context, in the tempo markings of the rhythm that plays; time in the durational context, in the length and composition of the exhibition pieces themselves; and time in the narrativic context, of the passing of time in the artist’s real life. The first time plays with the intricacies and minutiae of electronic music production; the second hypnotizes and immerses the audience in its flow, and the third connects the individual exhibitions to paint an uncapturable vision of an artist’s lifetime.

Posthumous exhibitions usually operate at a shortcoming, for this degree of narrativic time manipulation is often uninformed. Fortunately, in the darkness of this exhibition, the other two time-scale come into play: the music of Sakamoto himself guided me. His carefully planned soundtrack pace the rhythm, dictating the tempo of time, controlling our movements and sentiments from beyond the screens, a magician whose hands never rests. In the very timing of our steps, the artist exists, his shadow looming.

iii. the first time, hidden in the rhythm

Forgoing the larger scale of time movements, the musician usually obsesses over the more minor movements of time: the seconds that make up each beat, the tiny moment that separate each note. In his works, Sakamoto often drill down to the fundamentals of the sound: its physics, its form, its shapes and irregularities.

I have to admit that I was not too familiar with Sakamoto prior to the exhibition. Yet the moment I stepped in, I was reminded that Sakamoto is much more than a composer of minimalist piano melodies that can fit well into a lo-fi playlist (to defend myself, the fact that his first listed piece on Spotify is the piano version of Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence). This man was one of Japan’s pioneer in electronic music, and that was reflected in the exhibition theme of playing with sound in a rather mathematical and manipulative manner.

In the music of Sound and Time, Sakamoto borrows plentifully from his work in his 2017 studio album async, which as the name suggests, deal with the idea of distortion, of time-out-of-frame. Time, so fundamentally built into music, is often ignored until its conventions are broken. In the piece ZURE, two sounds, a pad and a click, starts of together but each moving at a slightly different pace every measure, gradually falling apart over the five minutes of the song.

Electronic music has long played with complex timings. On the screen, one sees measures readily laid out, as if inviting one to play with them. The first time, with its rhapsodic dances, exemplified Sakamoto’s and a generation of producer’s playfulness with time. The first piece in the exhibition allows one to play with them too: as one dials the switch, the frequency of particles on screen changes with the music.

What an absolute fervor electronic music must have been in the late seventies, when Sakamoto and two friends founded Yellow Magic Orchestra, one of the pioneer electronic music group in Japan. Through Sound and Time, I relived that moment, as I am invited to mess with sounds, to indulge in the childlike wonder and ingenuity of manipulating sounds. In electronic, the potential for sound manipulation is endless - sound can appear nothing like their source material, completely transformed during the processing.

iv. sounds, given form

The performance of time has to be given a shape: here, it takes on light and water as two main forms. In darkness, there is light; the light of the exhibition tracks the delicate calculations in the music.

In the exhibition centerpiece, nine water tanks are suspended on air, filled with water and fog. On them, images of excerpts from Sakamoto’s opera Life are projected. As the colors and images shift, the soundscape also changes: still, dark and monochromatic sequence accompanied by quiet, eerie music, while bright and vivid sequences accompanied by louder, more jarring music.

In another piece, the music grows increasingly unnerving as common objects are very slowly replaced with blurred lines of their silhouettes, in a series of videos. A seemingly consonant motive becomes gradually littered with more dissonant musical chords, eerie synths, and straight up industrial noises.

Sakamoto’s music rarely reminds one of grandiosity. Apart from some tracks in his early electronic compositions, his more popular music has leaned on the simple, cosy, minimalist-sounding aesthetic, the kind that would fill a small room, the kind to be listened to privately on headphones. A large part of his music is film scores, music meant to be accompanying a greater narrative, rather than standalone. It is surprising, therefore, to see his music being given a form so grand, so overwhelming as in this exhibition; to see his music be the main star of such large-scale works.

The exhibition is beautiful about artists from different disciplines coming together to create a piece is something that Sakamoto must have keenly understood himself, with his extensive collaborations as an electronic and film composer. Thanks to that, here his music takes on multiple shapes: dusty visualizations, vibrant and eerie video channels, moving rhapsodies of water, meditative cinematic collages. The music moves beyond itself, into a part of a larger whole, as all the senses grapple with the complexity of the exhibition world.

v. the second time: the mesmeric draw of space

The presence of the second time is characterized by an absence of another time: the real-world time, the time that actually passes as one walks through the exhibition. It is as if the complete enclosure of the exhibition also separates its time-physics from the real world clock, turning it into a volatile liquid at the mercy of the artist’s rhythm. I almost lost track of time in the exhibition. Usually I would find it challenging to sit still for ten minutes in front of a screen in an exhibition - I had no problem doing it here.

There are other people in the exhibition too - they are slight and silent as phantoms, leaving hardly a resonance in the air. The exhibition welcome us like no other, inviting me to make myself at home, to sit, to lie, and to burgeon in the velvety darkness.

With the complete darkness and absence of sound, the artworks are mesmeric. One can even say it’s voyeuristic. The audience was taking a peek into the artist’s mind, his private, personal space. Sakamoto is famous for being a private person: he offers little interaction with the public outside of his works. Yet the works possess such genuineness and sincerity that one feels so drawn to, so compassionate of this distant persona.

The world conjured up by music, sound, and light seem to have no duration: it is a constant, only separated from us by screens, water tanks. Aside from the movie installation in collaboration with Apichatpong Weerasethakul, none of the works have a set duration. Most of it is a meditative cycle of darkness. The sound develops, yet they they never relent or fade out. Time seeming stops, or never matters at all.

vi. the sound, the elemental.

In the exhibition, the theme of water would recur, mainly through Sakamoto’s collaborations with …. Through water, the artists explore another way for movement to create sound, and for sound to curate an environment, an atmosphere.

Even in classical music traditions, composers have been keen to portray the water sounds. Water, fundamentally sonic in its movement, draws out images. The French impressionists take the portrayal of water to a new height, with pieces like La Mer or Jeux d’eau from Debussy, or Une barque sur l’ocean or Ondine by Ravel. On the piano, ripples and high arpeggios become the quintessential sound of water. Sakamoto continued that tradition in his installations, working to draw out sound from water, rather than simply imitating them (though his frequent use of crystalline high-pitched piano cluster chords suggests he is plenty interested in creating impressions of the water sound themselves).

Water in the exhibition is pure: crystalline, transparent, mirror-like. Yet, even in its elemental form, water is infused with the affectations of sound. It becomes an actor on stage rather than a natural spectacle; it is almost conscious of its surroundings and behave wilfully under the guidance of the music. The most serene piece of the exhibition, just a room across from the centerpiece, titled ‘water state 1‘, demonstrates this. In the middle of the room sits a water bath, paved with grey slate. From the top, droplets of water fall into the still surface, creating ripples. Big rounded rocks sit around the room, clearly inspired by Japanese gardens.

Just like our ancestors have harnessed nature into a miniature garden, the artists harnessed the miniature garden into a geometric form, compliant with the laws of sound. The seemingly random rainfall was calculated according to rain data in Japan. The vibrations from the ripples are sensed by sensors to modify the music inside the room. The sound of water is now detached from it’s original shape, augmented by computers: it is the sound of human and nature at the same time.

The theme of using water movements to illustrate sounds would also underpin two other installations. In the water-tank centerpiece, the water’s movement also influences the music, this time with the addition of fog. And in another piece, the water paints a deluge on screen, a series of undulating waves.

The elemental augments the second time: since nature’s sound is endless, the sound of the piece is also endless. It adds to the sense of ease, of serenity, of lingering wist as one walks through the exhibition. Even on a stage, nature is powerful. Even modified and hybridize, nature relays its elemental power.

I can’t stop thinking about how even when sounds are so elemental, their underlying workings are so complicated and ingenious. In ancient time, who could have thought one day we would be able to dissect the sound of birds, of horns, of the rain, into soundwaves; that we would be able to transmit those sound waves, burn them into a disc, into numbers on the cloud; that we would be able to modify and manipulate those sounds beyond recognition to create whatever soundscape we desire, unlimited by the offerings of the universe? As sound got dissected, however, it would never lose its primordial power. While nudging us to look at sounds more analytically, the pieces also emphasizes the spiritual nature of sound, of its serenity and turbulence.

vii. the third time: questions of existence

In the third time, Sakamoto’s phantom hands would walk me through different stages of his life, through almost twenty years of installation work condensed in two-hour experience. In that flow, one confronts the question of transience. The exhibition form, is transient. The human’s work, is also transient.

It is peculiar that an exhibition of music and sound design would have me contemplating about existence and reincarnation. Yet exhibitions, by their nature, are reincarnations. Every time an artwork is staged, performed, or reproduced, it departs slightly from its original self, only keeping its essence. When each of the artworks in Sound and Time was reconstructed into a whole after they have been individually exhibited, that is their reincarnations. The pane of glasses themselves are different, and the water is changed, but the idea persists.

Any artist of worthy merit would never be complacent. The Sakamoto of these installations must have grown weary to the small scale musical experiments of the eighties - he desired for his works to grow vaster in scale, more fundamental in spirit. He worked with ways to manipulate sounds into visuals. The artist’s maturity translates into the remarkable sense of introspection in all the works of Sound and Time. Both the delicate tinkering of the first time and the total immersion of the second time allow the audience the silence to meditate and reflect with the artist.

Delving a little deeper into his life, I get the impression that Sakamoto was always searching for something of a pure, spiritual expression through art, whether he was making iconoclastic electro, polished lyrical pop, or minimalist ambient piano music. He is a rather private person who was also passionate about social causes, especially environmental. Sound of Time has an out-of-time feel, almost an eternal silence. All the noises and chaos that inform his life is distilled down to minimal expressions and symbols. It is a surprisingly accomplished attempt in capturing the spirit of the artist’s lifetime work, a colossal task considering his vast discography.

Immersing oneself in that spectacular environment is also burgeoning an acknowledgment of temporality, a regret of impermanence. Whatever I was seeing existed in that moment solely, impossible to be recaptured. Any attempt to capture is meaningless, or rather pitiable, since the works are so extensive in length and scale that cramming it into a single still moment in the frame is a travesty. The water flows, continuous, through-composed, unrelenting and never repeating. The music shifts, swells, and subdues, seemingly stochastic, never following a through line. Even in the videos I tried to take, the essence of the work escapes its form.

There I was, treading both the hopefulness of the exhibition undying, and the despair of the exhibition uncapturable. The moment I step out of the exhibition, it will remains no more than impressions; through writing it down like I am doing now, I would attempt my best to reconstruct it from the exhibition booklet and whatever pictures I could take, but its spirit has already departed.

Life is serendipitous, magical, short-lived.

viii. finality and decay

Near the end, after there is all but one room left, I was led into a corridor. Light flooded my eyes. In the corridors, I encountered the first texts of the exhibition: a complete timeline of Sakamoto’s life and artistic achievements. In a sense, it is my first time learning about the artist to a reasonable degree, beyond his most popular mainstream works. It is rationalization, the shape of reason, cast over the immense spirituality of the exhibition itself. Putting this information at the end of the exhibition instead of at the beginning as per convention is a great move from the curators: instead of letting text dictate the audience’s experience, they let the artwork speak for itself, in all its enigmatic glory, and then attempts to contextualize them.

Upon entering the final room, there was a simple but menacing warning on the door: End of exhibition, do not turn back. I felt it was meant with grave sincerity, a final warning before the exhibition fades into memory. I realize I failed to take any picture of this last room: such is the great irony of remembering.

In the final room, there was a piano in the center. Surrounding it is flashing lights on the sides that turns on and off to the off-kilter rhythm of ZURE. I found it weird that a still piano would be the centerpiece of an art piece that is clearly electronic.

The piano, by itself, without any intention to be touched, clearly indicates a gaping void, that of a performer. This sound-artificer has been stripped of his songs, it is now only a form without function. The water around it stands still, sensitive. For all the deconstructions of sounds, the most fundamental of all music, the acoustic instrument, remain helpless.

Instruments will decay, such is the inevitable way of time. And with it, sound will have to decay too. A fundamental identifier of a sound is when it will stop. Everything must eventually quiet, the silent piano seemed to say. As the electronic music keeps on building, the centerpiece has resigned to its inevitable end. The music can keep on playing, but the player can’t keep on forever.

The piano was Sakamoto’s first instrument, before electronic music. His last movie, OPUS, was him playing piano transcriptions of his wide repertoire. Inside the piano, it seems like his spirit has finally returned to its infant form. Time is a circle. I listened to his unceremonious farewell before walking out into the light of the merchandise store..

It took me too long to write this - almost 6 months now, so the exhibition has long closed.