To say that Edinburgh is picturesque must be an understatement, for no city I’ve been to seems to have accomplished such mastery in the art of arranging its buildings to create a photographable view. In Edinburgh, chasing down spires and lamp-lit windows amidst its lofty hills, as the wind flutters in one’s flushing face, the traveller felt almost enveloped by a rogue sense of history and mystery, the kind that infects any romantic’s addled heart with the inscrutable malady of nostalgia.

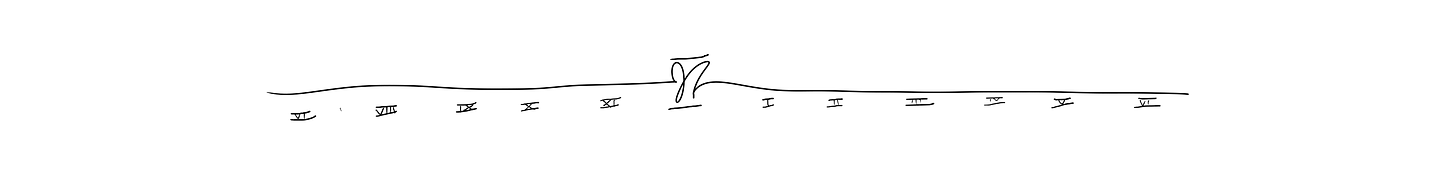

From Waverley, heavenwards; from the swampish depression scarring the city’s heart, right to the doorsteps of its towers. Immediately, the small city1 took on colossal vertical scale, as the buildings staggered on both side of the ascent, layers upon layers. Encumbered with the luggage, the traveller could barely help but feel like he was witnessing a god-blessed theatre set piece: every structure aligned so delicately, so masterfully as to maximise the illusion of grandness. Its centerpiece, The Walter Scott Monument, somewhere between a delicate ritualistic sculpture and a savage thorn growing from the mutant body of Princes Street’s Garden, felt so outsized that one can be fooled it was dedicated to royalty or even God, instead of a writer, albeit the nation’s most celebrated one.

The Edinburgh castle - the city’s grand dame - reigns on a crag right above Waverley. On that rugged, dramatic volcanic throne, she is chivalrous, yet remarkably romantic. Such ambivalent entities castles are, almost the pinnacle of the romanticisation of conflict, of the art of turning brutal battles into shining knights, and heinous politics into lavish royal feasts. The Grand Dame of Edinburgh is no exception: she wields the worn lapels of her stone coat as if they were silken; so graceful is her stance that even her battlements feel like decorous taffeta, almost obscuring the bloody history she has witnessed. Downhill, tender glimpses of the past enveloped the castle’s environs, and I can almost see the faint breaths of Scottish soldiers, climbing up that precarious cliff to ambush the sleeping English, engraved in the terrain.

In the vicinity of the Old Town, Edinburgh herself unwound in front of me, her gravelled roads undulating like ribbons, tucked beneath one another. On the upside one notices the magnanimous facades of churches and institutions, new and old alike, the likes of St Giles Cathedral and the National Museum. On the downside one notices barely-ventilated windows in the knots of gravel, the past shelter of immigrants and workers. Our kind tour guide for one morning invited us in for a glimpse of an old basement in one of the cities’ backlog of terrain. The ghosts of illegal distilleries, prostitution and death filled the air, in quasi-reality, emboldened by the city’s mystical inclination. This city of kings is also one of the fae of soot-blackened poverty.

Hills, the ends unbound. On the gentle descent of the Royal Mile, slightly away from the bombardment of souvenir shops selling the same magnets, cashmere scarves and Harris Tweed purses, one might look up the various closes of Edinburgh to find a tiny garden to shelter one from the bristling wind. To the end stand two venerable yet contradicting structures: Hollyroodhouse Palace, resplendent in excessive classical architecture, and the Scottish Parliament, an even more maximalist canvas of Spanish cubist sentiments cobbled together through pure entropy. Yet, these giants are somehow overshadowed by the grand park next to them, whose beauty implies a sense of bewitching wilderness not conceivable in such an urban environment. The grass is pale and haywire, the green dried out by the breath of winter, the bed of dirt road still supple to the touch; suddenly, one finds himself caught between a crystalline lake at the bottom and the grand backdrop of Arthur’s Seat in the distance.

Edinburgh, an ambiguous urban hybrid, possessing all the gravitas of an important historical city and the subtlety of a quaint town. The theatrical drama of legends towering over the humble shadows of terrace houses - launderette, book clubs, Chinese grocery.

At seven, the city is bright, but still slumbering. A gust bursts through my scarf. For a moment I am a fluttering wick, the next I am bathing calmly in the chill. The tram down to Leith is leisurely, soundless even - our fellow Edinburghians move in with a tranquility unimaginable in London tubes. The city flows by without much resistance. Bricks turn to papier maché. Invisible glass flowers in the air. Towards Leith, a herd of seagulls practicing choreography on the precarious old docks. The Firth of Forth - what a evocative name, carrying breezes between your teeth as you pronounce it - opens up in the distant horizon, its waters serene and silent.

Even the less decorous parts of Edinburgh are alluring. The gravelled road disturbed by construction work, whose dirt has been scattered by the persistent rain. Old terrace mansions, moss fading into brickworks, the peeking yellow of freshly planted narcissus. The small bridge over the water of Leith - what a peculiar moniker for a river, the width of a passageway, enamoured with the nonchalant joie-de-vivre of floating plant debris. A Costco under a working-class tenement. Again, the water of Leith, whose reflection shivers in the misty drizzle, like spells brewing in a cauldron of black earth, occasionally revealing glimpses of mythical paraphernalia buried beneath its frigid waters.

People in Edinburgh walk like ghosts. Not because of a sullen, misanthrope outlook that one sometimes associate with citizens of the cold countries - the Scots I’ve met are much warmer than their southern neighbors even. They walk fast, yet there is an inexplicable calmness to their brisk pace, almost like gliding on the stone pavements. They speak with windy syllables and a hushed politeness. A phantom-like austerity follows them around, the indelible nonchalance, reminiscent of someone who had left the world behind.

In winter, Edinburgh doesn’t give one much time to do the touristy things: most attractions and shops open at ten and promptly close around five. Around six, the wind starts to pick up, yet the sky retains a ghastly gray indifference. One yearns for a sumptuous dinner, a fiery dram of smoky whiskey to revitalise his body, yet the shops are empty and feel almost unwelcome with light still draping over the horizon; being a tourist and therefore especially careful not to take too much liberty with local customs, the traveller returns to the street. In certain circumstances, such aimless wanderings can become almost clinical and torturous — god bless the lost souls waiting for a delayed flight — but fortunately, Edinburgh’s gothic sentiments had protected it from turning to an airport terminal.

Silence falls on Leith Walk. Roadside shops have shut their droopy eyelids. The air is crisp and almost audible. The soundless shuffle of the people becomes even more intermittent. The trees are wistful, trying to cling to the final traces of color on their countenance. The glare of the bus, this bright mobile castle full of people, briefly feels like the only anchor one have to modern times. On the stage, the intermission act drags on, the cast wanders around aimlessly, and nothing seems to be in its right place.

Finally, as the last drop of light has devolved into a blurry mauve, one finally gets to tuck into the comfort of the restaurant. The first dram of whiskey is always the sweetest. By the time I leave, the castles are but reduced to shadows, and the streets were empty: all convivialities had been moved inside pubs, where all the ghosts of Scotsmen will go when their world turns to dust.

Edinburgh is decorated with millions of spires. Wherever one goes, the Scott monument is unmistakable. Surely, the fact that such a grand structure is somehow dedicated to a man of letters instead of the sword must have reflected the Edinburghians’ romantic inclinations? And surely, since the moment I set eyes on the monument outside Waverley station, I have been so impressed as to unwittingly adopt an indulgent, Romanticism-fueled outlook on everything else the city had to offer?

Through its blackened lens, one sees spires everywhere. Not just on top of cathedrals, but also in the modest pointy hat of roadside apartments. Haphazard chimneys, ceremonial vestiges of simpler times without gas heating. The trees are bursting out into spires too, their leafless branches jutting out, entangled, fractalised. White lichen covers their skeletal bodies. The Gothic spirit, deathly but graceful and magnificent, has spreaded to every corner of my vision, like an unshakable malady.

I imagined its anthropomorphic representation: a woman with vitreous skin, needle-like hair, and a savage gaze, dressed in the vivid lace fractals of flora. She has the frail severity of McQueen fashion models. Edinburgh is so beautiful she almost doesn’t feel alive, like how an old dame can look most spectacular when life had just been drawn from her breath, the years of toil vanishing with it, returning her to a pristine, maidenly state of decay. She had constructed a glass wall around her breathtaking post-mortem beauty, and I feel like a ridiculously clueless outsider, being obsessed with a beauty I can never fully grasp.

Back to my first day, under the grand dame of spires, a siren was singing with her donation box, her frail stature against the ghastly wind, her falsetto levitating like a disembodied folklore. Behind her, the plain, aloof classical architecture of the National Gallery, and beyond that, a moribund sun.

Quite uncharacteristically, Edinburgh greeted us with a few sunny days, a rarity for the Scottish February. And yet despite this, when I think of Edinburgh it is as if my mind had insisted on applying a diaphanous film of fog over its pictures, for in every degree of clarity there is an equal obfuscation. I was rather puzzled to see that I didn’t manage to take that many photos of Edinburgh - and most of the time, whatever magic that made the city so picturesque is diluted terribly through the camera. Sometimes a corner so agonizingly picturesque manifests themselves; unable to separate the tremulous breeze from the melancholic moss, the dangling seagulls from the scenery, I had no choice but to let the moment slip away like a crumbling morsel of yellowed paper, carrying a single prose line in a language one half understands.

The Edinburghian streets go in circles. Up and down their mystical corners, three days felt like a blink of the eye. No matter how many times I strolled those demure streets, no matter how mundane the terraced blocks on their sides had become, I keep returning to those blocks where the ghostly steps of people can be heard.

I had fallen in love with Edinburgh like I had rarely with cities before. I had become beholden to her magnificent beauty, her quaint pretenseless charm and her enigmatic silence. I was willing to relegate my sanity to her grace for no concessions. It is not the kind of materialistic love where you rank cities on the scale of one to ten, on walkability or crime rates, on cuisine or housing, but rather the instinctual desperation to idolise and dramatise. The love you feel in your bones even if you can hardly recall the colors on the face of that who you love.

Darkness falls like the curtains of an old cinematheque. I glanced back. The castle battlements gently peek out from atop buildings, almost ghostly and ethereal in its grace, as its stern masonry becomes softened by the crepuscular touch of colors. I had not gone very far. And not very far I will go. Nothing but pubs will be open as the streets turned into chilly puddles of shadows. But Edinburgh, my heart is always wide open!

no doubt a monumental city, but with 500 thousand people, Edinburgh is a village by Asian standards