Disclaimer: This essay is less to discuss dreams scientifically than to provide an artistic view of them in relations to films. Since I am not a professional psychologist, there might be scientific inaccuracies in the following content on dreams. I would greatly appreciate any feedback on that.

Dreams represent a inherent part of the human experience that remains rather elusive to science. What is it about this almost universal, yet enigmatic experience that keeps on eluding the grasp of psychologists? Until recently, we still have not developed a consensus on why dreaming occurs, or what dreams mean.

With the deficiency of science, people has long been using art forms to depict and to make sense of dreams. From the ancient arts of divinity, to the more visual of paintings and photographs, to the aural of music. Yet it was only with the advent of cinema that humanity finally arrived at a medium that can adequately captures the characteristics of dreams.

Here I am not concerned with the purpose of dreams - for this is irrelevant to our analogy with film; rather, I am concerned with their materials and how they come to be. Doing so hopefully illustrates the various commonalities between the qualities of a film and a dream, and illuminates how film is the perfect medium for portraying the subconscious.

My motivation for this essay is my obsession with movies with a dream-like quality. Part of it is because I think they play to one of the biggest strengths of cinema. Part of it is because it offers so much potential for understanding an ancient but much obscured part of the human psyche. I get frustrated with the idea that a movie requires a clear narrative to be worthy of a watch, and that dreamlike movies are dragging, pointless mental masturbation. I would suggest that these people go read a book, or play a video game, if they so desire their narratives. For a film, the dreamlike is inherent, and this medium is where it burns brightest.

Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams was a hallmark attempt in deciphering dreams. Freud believes that dreams are encoded messages, often of taboo subjects and therefore requiring obfuscation from the mind. Despite the now-memeable reductionism of childhood trauma and wanting to have sexual intercourse with your mom, it had great contribution to the material of dreams: that dreams are made of childhood and recent past, that dreams, designed to be secretive, often deal with substitution and perversion of languages and objects, and so on.

Regarding Carl Jung, another influential dream scholar, dreams are established to be a method of entraining subconscious thoughts into narratives, a way for the mind to make sense of its own experiences. Unlike Freud, he did not believe that dreams need to be interpreted in order to be helpful: simply allowing the dream process to happen is enough. He also rejected the ideas that dreams often deal with taboo subjects.

Onwards to Calvin Hall, dreams are said to be an individual’s way of visualizing concepts within the mind through symbols. His research, the first proper attempt to quantitatively assess the cognition of dreams, relies heavily on dream-symbolism. Symbols are the anchor of dreams, and measuring the occurrence of certain archetypes of symbols (animals, death, sexual aggression, etc.) within dreams can provide much insights into personalities. This conviction that dreams has a concrete meaning, which can be dissected through the studies of symbolism, provides the foundation for much of contemporary dream studies.

Another influential and controversial scholar, Allan Hobson, rejected the ideas that dreams are of any psychoanalytical meaning altogether. Instead, dreams are just mere clumsy attempts by the brain to process chemical changes in the brain. Therefore, while dreams might offer insights into brain workings, their actual content are nothing of note and is worthless probing into further.

Regardless of their purposes, the appearance of dreams is something we can all agree on: confusing and nonsensical narratives (if at all), obfuscation of objects, humans, and experiences, the reoccurrence of certain symbolism.

A close look at the dream characteristics offers many similarities with films. To begin, film’s language, like dreams’ language, are profoundly visual. Importantly, films are capable of conveying visuals and movement without revealing to us any of its underlying agendas: the director, in assembling the film, is acting like our brain, using materials we are somewhat familiar with with significant artistic discretion. The results are surreal sequences, out of place sets, eccentric characters, and random, incomprehensible plotlines.

The visual-ness of films also enables them to play with symbolisms, sometimes displaying them recurrently to emphasize a certain importance, or sometimes concealing them in plain sight to foreshadow later events. Symbols in films can be made ordinary and non-intrusive, with their significance only fully understood much later into the film, which is analogous to how dreams employ ordinary symbols to conceal latent messages, if you are inclined to believe Freud and Hall. Hence, the analysis of films through symbols and their importance in narratives undeniably strikes a comparison with Hall’s study of symbols in dreams.

Secondly, despite their questionable coherence, dreams are irrefutably characterized by a forward progression: there is a sense of time passing as we dream. For this reason, static works of art (like photographs or installations) rarely fully conjure the dream-feeling. Film takes this even further, since the nature of cuts in films are very similar to that of transitions in dreams: they are often distilled, discontinuous version of reality. Just as dreams can leap wildly between seemingly unrelated subjects, films also can (or more precisely have to) make cuts and piece together scenes to advance. In a sense, the very limit of film, its artificiality, lends itself perfectly well to capturing the sense of progression in a dream!

The final similarity, which I find particularly intriguing, is that film is an illusion. Despite presenting itself as something real and immersive, deep down, films and dreams are both merely illusions without any particular effect from reality. Yet one only sometimes has control whether we want to participate in this illusion or not: sometimes one cannot wake themselves up from a dream, just like they cannot turn off a film playing in the cinema. This sense of quasi-reality, this balance between the real and the unreal, is another attribute that unites films and dreams.

Linked to this, a particular advantage for a film when emulating dreams is that its language is ambiguous between the ‘real’ and the ‘unreal’. The very nature of cuts is indifferent to the real and the unreal, allowing a smooth transition to take place, while in a book where the narrative is regarded with higher scrutiny, an out-of-place passage can be immediately regarded as a dream-sequence. Consequently, film is perfect for concealing the reality of a given moment until it ends - very parallel to how in real life we only know for sure something is a dream when we are awaken.

To illustrate this further, I do want to list down some of my favorite dream-movies down here - some taking the meaning of the word “dream” more liberally than others - with a short analysis of the dream-film relationship. Hopefully this shows the various approaches to portraying dreams on film undertaken by various greats of cinema, and convinces you that film is truly unsurpassed when it comes to emulating dreams. Mild spoiler alert for all.

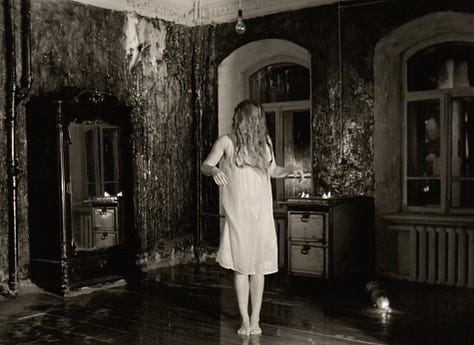

i. Mirror (1979)

A classic dream movie - reminiscent of literary greats like In search of Lost Time and Ulysses with its relentless throwbacks and stream-of-consciousness thinking, respectively, Mirror revels in recollections and enigma, representing the autobiographical aspects of dream. For what is the material of dream if not involuntary recollections of the past.

An autobiographical movie is not automatically dreamlike - in fact, Mirror is probably in the minority. What is important here is how the movie treats the autobiographical materials. Mirror really illustrates how you can control the specificity of portraying a dream in the medium: while alternating color schemes (black-and-white, sepia, and color) provide some indication of the timeline, its surreal mise-en-scène obfuscates details at the director’s will. Hence, everything exudes non-specificity - the sense of not-being anywhere, the sense of lost-in-space-time.

Note that the movie does not recount events in a chronological fashion, or in detail at all. The dream treatment of memory is similar to one letting an object cast a shadow on the wall, then using the outlines of the shadow to improvise an impression. While certain important details are preserved and keep the movie grounded - for instance the mother’s working stint in the printing press and the vivid memories of war - Mirror readily unravels into fantastic realms. Suddenly water was falling from the roof, people were exchanging identities, poetry was floating in the air as one nears their deathbed.

In In search of lost time, even though the character experiences a lot of involuntary memory, the very structure of sentences indicate that there is an existent and very obvious thinking process going on: the person is aware of his recollection of old memories. Meanwhile, in film, the character might just exist in the environment, and the scene does not necessarily impose an intent or direction on the recollection. This attribute makes the movie especially dream-like compared to a book, in that it is more accurately represents an involuntary, directionless assemblage of past experiences.

To speak of the dream-as-an-assemblage, dreams which offer little opportunity to dig deeper, but merely serve as a testament to the wondrous and eccentric treatment of source materials by the human mind, one cannot get much better than Mirror. Not arbitrarily is it a very revered movie by directors: it is an immense intimacy with filming techniques and the power of narratives that can be told through dreamlike montages.

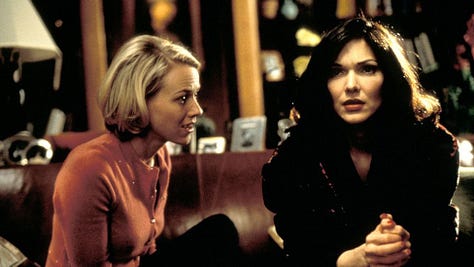

ii. Mulholland Drive (2001)

Mulholland Drive focuses on the drama of dreams. Dreams love to obfuscate in their presentation by altering small details and substituting objects. Here the same is done by David Lynch: through substituting characters, objects, and settings, he spins a straightforward narrative into a melange of whirlwind whimsicality.

This is a prime example of the psychological inner workings of dreams manifest on cinema. The film emphasizes dramatic, surreal cuts, obscure symbolism, and a general disregard of logic - all distinct qualities of dreams. The quasi-linearity of the film - events seemingly happening in chronological order but which offers so little logic one cannot be entirely sure - adds immensely to the thriller qualities of Mulholland Drive, turning it into an irresistible thriller first, and a dream-movie second.

In the famous ‘Club Silencio’ sequence, one can see clearly communicated the idea that films and dreams are both illusions. The film warns us, in our face, that it is a lie, yet we still cannot help but be sucked into its vortex of half-reality.

If one follows the mainstream interpretation, then Mulholland Drive is a very obvious example of dreams serving to fulfill a wish. Anxious characters use the dream to project what they want to happen in real life, the same way I would dream of passing a job interview days before attending it.

Here one sees the capability of the film medium in keeping its narrative ambiguous: not until the the final moments of the film do we have the necessary pieces to put the puzzle together. It is easy to at first dismiss Mulholland Drive’s narrative as pointlessly dreamlike, making the revelation of its true narrative even more shocking.

Due to its thriller qualities, Mulholland Drive also is a prime example of the dream-as-a-puzzle (as contradicting Mirror’s dream-as-an-assemblage). Despite David Lynch’s unwillingness to assign a clear solution to a film, it is undeniable that the film, by design, invites us to forage for a solution. The usage of symbolism, the sprinkling of clues, creates a sense of meaning for the film, even though we don’t have a satisfying interpretation. This is all again very similar to Freud’s early effort to interpret dreams: there is a meaning hidden somewhere, however obscure, and to experience a dream invites us to make sense of it, even though we might jump into conclusions like a woman’s dream of flower arrangement represents her urge to be deflowered (?!).

Note: the distinction between the dream-as-an-assemblage and the dream-as-a-puzzle is reminiscent of the central conflict of modern dream studies, between Hall’s and Hobson’s thinking: whether dreams are just meaningless signals, or are they by default cryptic messages to be deciphered.

iii. Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

One might not be inclined to believe that Moonrise Kingdom is a dream movie. In fact, it is not. However, I would argue that the film medium has the potential to impart a dream-like quality, even though the film itself expressly declares to be realistic.

There is no non-linear narratives, no object substitution, no autobiographical aspects here - aspects that we have discussed that are very characteristic of dreams. Most of the dreaminess is handled merely by the visuals.

This film (and more generally Wes Anderson movies) benefits from a very specific type of aesthetics that is the Wes (TM) - so famous that it prompted much imitation on social media. Angular framing, pastel colors, eccentric characters - you name it. This accomplishment is very specific to the film medium: no other medium allows so much focus on the visual aspects, which we have established is so essential to dreamlike qualities. Visual eccentricity, pursued so consistently, helps to convey a sense of unreal-ness, akin to how dreams construct themselves in very stylistic and illogical ways. If one has to categorize, I would say Moonrise Kingdom represents the dream-as-a-vision: the dream, despite lacking a lot of qualities that would make it a full-fledged dream, remains unmistakable thanks to its outstandingly dreamlike visuals.

In Moonrise Kingdom specifically, the thematic focus on childhood and naivete accentuates this eccentricity even more. The characters are oftentimes absurd, their illogical actions unquestioned, all under the pretense of childlike naivete. Since the film presents the characters through such strange logic, but accepts it in such nonchalant common-sense, the dream-like becomes apparent: dreams are a similar environment where eccentricity is innate to its appearance.

If nothing, Moonrise Kingdom is a testament to how films’ intensely visual-oriented character, under a hyper-focused director’s vision, can create dream-like feelings without even resorting to any obfuscations or conventional dream-quirks.

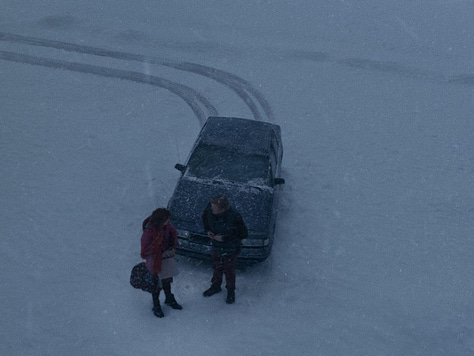

iv. I’m thinking of ending things (2020)

The newest movie on this list, I’m thinking of ending things probably offers the most fully realized dreamlike atmosphere: not only in pure incomprehensibility, lack of coherence, or expansiveness. In it we can find an ambitious combination of many dream-like qualities that appear in the previous three movies. The psychological intensity of Mulholland Drive, the surreal mise-en-scene of Mirror, the absurdity through aesthetics of Moonrise Kingdom, all combined to create a truly dreamlike experience.

In the movie, there is an enormous amount of human substitution: the confusion among the protagonist’s love interest, the rapid ageing of the protagonist’s parents. There is uncomfortable confrontation with childhood trauma, where the protagonist comes to an insanely awkward gathering with his parents where the film’s reality facde starts to crumble. There are surreal, dramatic sequences that defy logic, the most prominent being the dancing sequence towards the end. And in its final moments, the movie was very expressly a projection of wishes: of the man’s desire for love, projected onto an elaborately constructed castle of obfuscated desires.

Without saying much more, this is probably the most ambitious portrayal of dreams that I have seen (that I can remember). It is confusing and overwhelming, and necessarily so.

Dreams are ephemeral - no matter how hard we might try, there is no reproducing them. But films are permanent, and shareable. It took humanity millennia to come up with a technology sufficient to imprint our most primordial instincts on, so that we can dissect them, relive them, share them into a collective awareness. That is beautiful.